A fellow researcher, from Envision Kindness, where I found most of these beautiful photos, reached out recently about my 20+-year-old dissertation research on compassion. My research showed that in less than 40 seconds a doctor could, through direct words and actions, clearly display compassion AND reduce others’ anxiety (Fogarty et al, 1999). It was that simple. This got me thinking about the simple power of compassion I’ve seen in my work since then, and on the wellbeing of young people.

Compassion Defined

First, what do we mean by compassion? It’s not the same as empathy, which is our awareness of others’ emotions, trying to understand how others feel. Compassion is an emotional response to that empathy and a desire to act. To help. (Goetz, Keltner & Simon-Thomas, 2010)

Plenty of research shows the power of compassion (Avmaramchuk et al, 2013; Hoskins & Liu, 2019). Many studies also illustrate that compassion can be learned (e.g., Kohler-Evans & Dowd Barns 2015; Sinclair et al, 2021) but must be practiced (Hariman, 2009; Jazaieri, 2018). I’ll share a few stories from my work as a researcher.

The Power of Compassion

Compassion cycles. In a small suburb outside Nairobi, Kenya, I interviewed one young man for a health project. We were trying to learn the best ways to provide health services to high-risk youth. So, we asked them. I got the sense that no one had ever asked this young man his opinion. As he gradually realized my questions were rooted in wanting to understand his needs so we could respond with appropriate services, he went from confused, to shy, to understanding, and helping. He provided insights about where to locate services, who should provide them and what times of day. He offered to find others to talk to. It was a kind of compassionate cycle—as if my small display of interest and compassion inspired empathy and action on his part.

Compassion as advocacy. In a rural town about two hours from Islamabad, Pakistan, I was part of a panel discussing findings — partly in English, partly in Urdu — from a post-partum family planning project that had just ended. I don’t speak Urdu, but when the three young women who received project services spoke, I saw many in the audience cry. Later I learned the women had described multiple difficult births, seeing friends die in childbirth, and the fear they were left with. They described how family planning brought them hope that their bodies could remain strong and they could provide the best care for their families. The audience felt both the women’s fear and hope and were moved to action. Local district health officials committed to continue the services using their own health budget now that our project was over.

Compassion as connection. In a study of care for dementia patients in Maryland, USA, I interviewed one young woman whose mother was in the final stages of the disease. The mother’s personality had changed completely, and she only occasionally remembered the daughter whom she had talked to nearly daily until recently. Surely the daughter missed the relationship she once had with the woman she knew as her mother. But that’s not what the daughter talked about. Instead, she shared the joy of getting to know the woman in front of her, discovering what NOW made the mother happy, like pink butterfly hair clips. She worked to understand her mother anew and do what she could to make her mother happy. Her compassion took my breath away.

We each have precious stories of beautiful acts of kindness and staggering inhumanity. I hold both types of memories close. Together they make me human.

Learning Compassion

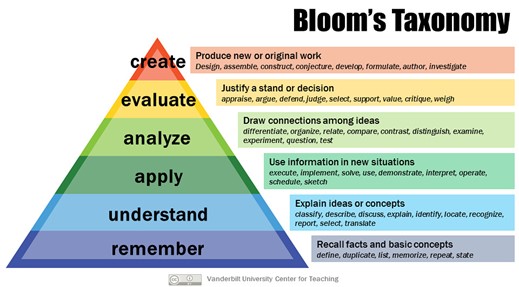

Now I work in the positive youth development (PYD) field at the International Youth Foundation. We are committed to the success of young adults and engage them to help identify solutions and guide project design. We emphasize life skills, such as interpersonal skills (teamwork and conflict management) and community mindset (including empathy and cultural understanding). Many of the lessons build on an awareness of others’ emotions and a desire to act: Compassion.

Life skills training in the classroom. Schools we work with in Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East value and invest in life skills, including empathy and compassion, and they are seeing the effects on young people’s wellbeing. For example, young trainees in Zimbabwe had increased subjective wellbeing in resilience, economic empowerment, and quality of relationships. Learners in South Africa scored higher in responsibility, problem-solving, goal setting, and desire to lead. First year high school students in Chihuahua, Mexico, with life skills training had lower drop-out rates and higher Grade Point Averages than other students.

Not surprisingly the in-person program affects not only students, but also teachers, many of whom are new to the ideas and the participatory methods they now incorporate. In an evaluation of our life skills curriculum — Passport to Success© — in Tanzania and Mozambique, teachers saw a mindset shift in themselves after teaching life skills. They reported valuing and using life skills in and out of the classroom. Most importantly, they reported prioritizing student success beyond graduation over enrollment and course completion, seeing their role as connecting youth to their future goals rather than simply imparting skills.

Compassion Takes Practice

While writing this blog, I unexpectedly found a powerful TEDx Talk from June 5, 2018 called “How 40 seconds of compassion could save a life.” The speaker, Stephen Trzeciak, a physician specializing in intensive care, listed the research evidence on compassion and its benefits for patients as well as providers. Knowing the research well, he turned to our 1999 “40 seconds of compassion” paper when he faced his own work crisis. Rather than treat his burnout by escaping — the recommended therapy — he hoped to heal by reestablishing personal connections. He diligently added moments of intentional compassion into each patient interaction, practicing compassion until he felt it return to his life. In his words: “I connected more, not less. Cared more, not less. I leaned in rather than pulling back. That’s when the fog of burnout began to lift. My 40 seconds of compassion changed everything for me.”

I’m left with this simple reflection: Compassion. Is. Powerful. Understanding it more, teaching it more, practicing it more could change everything.

References

Avramchuk, A.S., Manning, M.R. & Carpino, R.A. (2013). Compassion for a change: A review of research and theory”, Research in Organizational Change and Development, Vol. 21, Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley, 201-232. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0897-3016(2013)0000021010

Fogarty, L.A., Curbow, B.A., Wingard, J.R., McDonnell, K., & Somerfield, M.R. (1999). Can 40-seconds of compassion reduce patient anxiety? Journal of Clinical Oncology, 17(1), 371-379.

Goetz, J. L., Keltner, D., & Simon-Thomas, E. (2010). Compassion: an evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin, 136(3), 351–374. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018807

Hariman, R. (2009). Cultivating Compassion as a Way of Seeing. Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 6(2), 199-203.

Hoskins, B., & Liu, L. (2019) Measuring life skills in the context of Life Skills and Citizenship Education the Middle East and North Africa: United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the World Bank. https://www.unicef.org/mena/media/7011/file/Measuring%20life%20skills_web.pdf.pdf

Jazaieri, H. (2018). Compassionate education from preschool to graduate school: Bringing a culture of compassion into the classroom. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 11(1), 22-66. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIT-08-2017-0017

Kohler-Evans, P., & Dowd Barns, C. (2015). Compassion: How do you teach it? Journal of Education and Practice, 6(11). www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online)