Over two decades have passed since the terrorist attacks of 9/11. Since that horrific day, the US has engaged in two overt wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, along with several more covert drone wars in Libya, Yemen, Somalia, Syria and Pakistan. Yet when we choose to #neverforget 9/11 (at least in the US), our focus remains on the lives lost on US soil and not the hundreds of thousands dead through direct and indirect warfare elsewhere as a consequence of US actions. Particularly in light of the recent US withdrawal after a 20-year occupation of Afghanistan that has left the country worse off than before, it is important for us to teach and learn a more complete, nuanced, and inclusive history of 9/11 together with its aftermath.

In a national survey of secondary school teachers, Stoddard (2019) found that the events of 9/11 and War on Terror are taught in US schools in an uneven manner and they are “treated rather superficially in many commonly used textbooks” (p. 2). Much of the focus on the subject is around politics, foreign policy, terrorism, first responders, and US victims. While these lessons have their place, they offer an incomplete and partial history of 9/11. This was corroborated by my team’s own research in 2019, when we conducted a curricular resources review of over 30 freely available curricula that have been published between 2001 and 2021. Similar to Stoddard’s finding, the bulk of these materials focused on US foreign policy, terrorists, and heroes. However, a glaring omission in the materials was the perspectives of people living in the shadow of 9/11. While we did find a parallel set of curricula that educate about Muslims and Islam, these seem to focus more on the basics of Islam rather than deal with issues related to 9/11, even if that was the impetus for their creation. In fact, none of the resources we reviewed paid any attention to the 387,000 civilians who have died as a direct consequence of US wars or the millions of people who have been displaced by these wars (Costs of War). It became apparent that a curricular intervention – one that was built on missing perspectives of the “other” victims of 9/11 – was needed.

In response to the lack of critical materials that focused on the ongoing consequences of 9/11, we decided to develop a curriculum that was grounded in the 20 years after 9/11. To begin our process, my team created a timeline based on a review of “newsworthy” media-reported events connected to 9/11. These included acts of war, terror, resistance, and representation of Muslims (and those presumed to be Muslim). We used the timeline (with over several hundred entries between 2001 and 2019) to identify themes that correlated with my qualitative research from the past two decades with youth from AMEMSA (Arab, Middle-Eastern, Muslim, South Asian) communities in the United States.

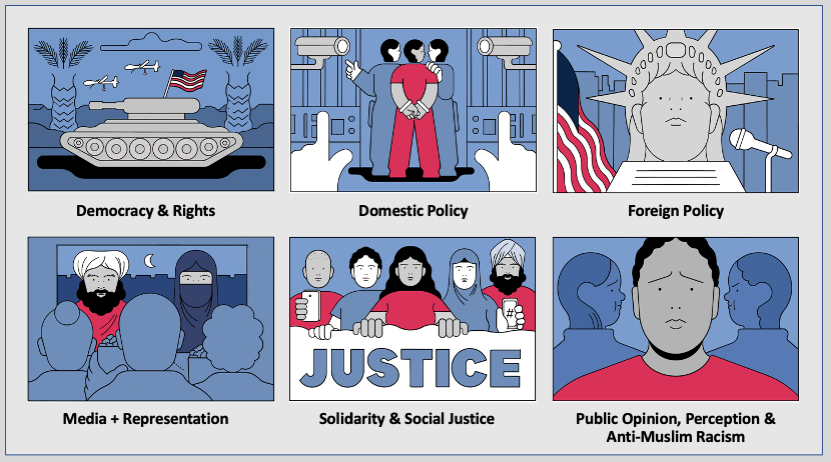

These endeavors led to the creation of the Teaching Beyond September 11th curriculum as a significant corrective to the missing perspectives and histories in available resources. The 20-module curriculum has been gradually released since August 2021 and invites learners to critically examine the history of 9/11 and to understand its ongoing consequences. Aside from the obvious themes of US Foreign Policy, US Domestic Policy, and Public Opinion, Perception, and Anti-Muslim Sentiment, we also included the themes of Media and Representation, Democracy and Rights, as well as Solidarity and Social Justice. The curriculum thus showcases young people’s activism and how organizations have been resisting discriminatory policies. Moreover, it strives to amplify the voices and perspectives that are missing or not given enough attention by the media or in the classroom.

In fact, almost all of our curriculum partners are from AMEMSA communities. This was really important to me personally. There are many scholars and practitioners who could have written these lesson plans, but I wanted to take an anti-imperialist, decolonial stance to push back against dominant narratives. As such, I strongly felt that having a team from the very communities that have been impacted by 9/11 policies and programs, either directly or indirectly, was the only way to create the kind of curriculum that really disrupts the commonly-told stories about 9/11.

This collaborative partnership between social justice activists and educators across the world has resulted in an innovative curriculum framework that is academically rich and pedagogically nimble, addressing both historical and current dynamics of anti-Muslim racism and structural Islamophobia. Stoddard (2019) identified several barriers to teaching about 9/11, such as lack of resources; fear about how administrators, students, and parents might react; and concerns of inadequacy when it came to facilitating discussion on this topic. With over forty lessons to choose from across our six themes, the curriculum not only provides educators with a much-needed resource, it gives them as much flexibility as possible when dealing with political and historical topics while equipping them with necessary knowledge to teach the lessons comprehensively.

The fifty-minute lesson plans (and extension activities) can be adapted to suit many different age groups though the target groups are 11th and 12th graders along with first year college students. The curriculum encourages a more nuanced understanding of the world since 9/11 so that learners can recognize the ways in which events across time and different communities are connected. As mentioned earlier, we used a timeline as the backbone of the curriculum and so each of the 20 modules is grounded in a particular event during a year between 2001 and 2020. For example, the 2006 module is anchored in the Abu Ghraib torture scandal that emerged between 2004 and 2006. We then connect it to the US Senate torture report that came out 10 years later in 2014. This allows students to see how events are linked through time and space.

Currently, 16 of the 20 modules are available and are free to download. There are multiple entry points for educators beyond social studies, history, and politics to include subject areas such as media studies, ethnic studies, religion, women’s studies, etc. The majority of the lessons are stand-alone and need not be taught sequentially. At the same time, we do build connections within the curriculum across events, time, and space in the hope that such wide representation will allow for at least aspects of the curriculum to resonate around the world. The curriculum thus serves as an invaluable intervention to support young people in developing a global point of view on issues such as anti-Muslim racism and xenophobia that extends beyond remembering 9/11.

To access the curriculum, please sign up here. For questions about the curriculum or to request a professional development workshop, please email: TeachBeyondSept11@gse.upenn.edu

Works cited:

September 11th Curriculum | Penn GSE. (n.d.). Retrieved July 6, 2023, from https://www.gse.upenn.edu/academics/research/september-11-curriculum

Stoddard, J. (2019). Teaching 9/11 and the War on Terror National Survey of Secondary Teachers. https://minds.wisconsin.edu/handle/1793/79305

The Costs of War (n.d.). Summary of Findings | Costs of War. Retrieved July 6, 2023, from https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/papers/summary