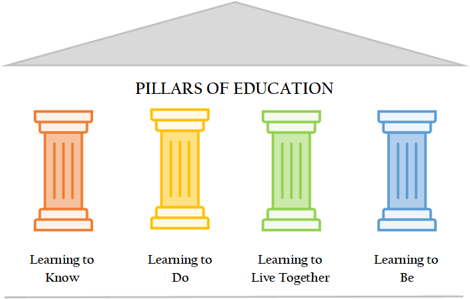

It is well documented that education is a human right and a necessity in modern societies, especially in emergencies and post-conflict relief situations. It is also known that transformation can happen through authentic, learner-centered, and quality education, hence making education an important tool for change. A major report by UNESCO (Delores, et al.1996) articulates well the role education plays in human development and identifies four critical components or pillars of learning for future generations that are worth sharing and exploring in this blog series. The four components are: learning to know, learning to do, learning to live together, and learning to be. This blog post reviews them and provides further thinking on examples in religious education contexts.

As an educator myself and someone who has accumulated experiences and learned lessons from working in conflict areas, I have witnessed the importance of all these pillars of learning to achieve and enable individuals as well as groups to change their lives. Transformation must involve creativity in pedagogy and curriculum along with addressing learners’ rights, starting with providing safe spaces for teachers and students to develop, make mistakes, and gain confidence. Unfortunately, the four pillars, representing a more comprehensive approach to transformation, are not always adopted, and acknowledged in schools and in higher education. This approach challenges change efforts because when only learning to know and do are prevalent, education does not fulfill its role of improving society, especially in countries with limited resources. As Schliecher (2019) suggests, the future of education is in combining knowledge and technological skills together with socio-emotional skills and values for humans to grow and develop. This is of great importance today especially since government emphasis on academic scores and rankings is losing the battle on socio-emotional learning and the values needed to improve youth and their lives (Kearns, 2010).

The learning to know component is very much focused on the transfer of knowledge and information; the educator is at the center of the learning process and holds all the power over information and its delivery, with the learners being passive recipients. This is the most common form of education where teachers provide new information to students which they are supposed to assimilate or accommodate into their existing collection of information, what Piaget calls schemas (Mooney, 2013). This knowledge ranges from basic reading, writing, mathematics, science, and memorization of the holy Quran and prophetic traditions in the case of religious education. In today’s realities of globalization and interrelatedness, learning to know is not sufficient by itself to prepare the next generations of leaders and citizens of the world as the information is available and accessible to anybody who would like to know more. Having the skills to identify, analyze, synthesize, and create knowledge is needed today more than the basic skill of learning to know.

The learning to do pillar is more about competencies and behaviors but also about technical skills and the abilities related to the physical environment and how we interact with it. For young children, it’s the ability to tie shoes, open a book, ride a bike, and put a puzzle together. It is also about having digital intelligence and learning to navigate the social media platforms and online world safely (https://powerof0.org/lifeskills/) or getting from one point to another using public transportation, a bike, or a map. In Islamic religious education, it entails learning how to pray, clean oneself, and finding the qibla (the direction towards the Kaaba when praying). The first two pillars work together to seek knowledge, navigate, and do. Although in the learning to do component there is a call for independence and mastery of life skills, online platforms today are flooded with trouble-shooting instructions on doing everything one can think of, like the information overload for learning to know.

Learning to live together requires a collective approach where government officials, policy makers, non-governmental organizations, and religious leaders spread the message about living with the other, starting with differences in the immediate local community. Recently, there is more emphasis on the learning to live together pillar of education through curriculum materials and global players who have been collaborating to promote the approach. One international example is the work of the Ethics Education for Children curriculum that has been translated into many languages and is in partnership with UNICEF and UNESCO as well as other international organizations (https://ethicseducationforchildren.org/en/what-we-do/learning-to-live-together). In religious education, there are also available resources by Muslim scholars to support the learning to live together. For instance, the works of El-Moslimany (2018) and Qurtuby (2013) speak about the inclusion of the whole world and all humans when thinking about the “Oneness of God” (Tawheed).

The fourth pillar, learning to be, goes beyond all three and includes the spiritual learning where one needs to feel safe to explore their state of mind in relation to self and others. The learning to be requires all three previous pillars to work together including the cognitive, social, and emotional skills along with values of individuals and groups to seek higher virtues to live by (Nasser, et. Al. 2019). These may be inspired by human as well as revealed knowledge of the holy Quran, the Sunna, and religious teaching. In addition, this pillar cannot be forced but needs to become a natural step evolving from and along the other pillars.

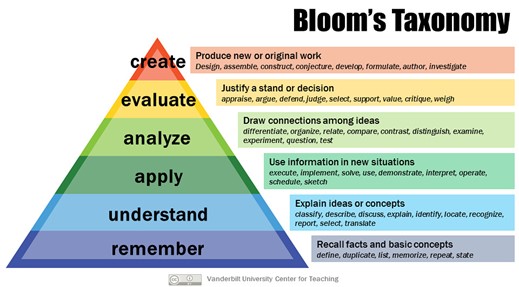

The first two pillars of education are more prevalent than the last two because educators have easier access to resources and ways to achieve learning objectives and there is more familiarity with them. The resources on knowledge and ways to teach skills are also available to teachers who are in the formal system and in non-formal settings of education. The learning to live together and the learning to be components are at an advanced level of learning (see below Bloom’s taxonomy and its hierarchical learning model described in Armstrong, 2010). They require further engagement of educators and students alike in terms of analysis, evaluation, and creating new knowledge (Armstrong, 2010). As mentioned, they entail a wider involvement of the immediate communities and stakeholders to model and reinforce the types of behaviors, values, and principles that strengthen the ability to live together, to be which also requires personal development, and to aspire towards higher states of consciousness (Nasser, et.al. 2021). Both pillars, in fact, aim at promoting a healthy and inclusive human development, especially elevating the spiritual and psychosocial aspects of learning. As such, in education settings, whether formal or informal, there is a need for a more intentional approach and emphasis on these two pillars.

To expand on the learning to be pillar and explore it further, situating it within the empirical and field-based scholarship, this blog series focuses on learners in PK-12 and higher education, especially in Muslim communities, to discuss the aspects of growth relevant in promoting learning to be. It shares recent studies examining youth wellbeing, sense of belonging, ethics, curriculum, needs of students in schools and universities, as well as how teachers respond to the pedagogical requisites of students. Our Mapping the Terrain empirical study on Muslim youth, educators, and parents in Muslim societies highlighted the critical need to explore the learning to be as a critical state of learning and its manifestations in self-development, values, and competencies among participants in 15 Muslim countries. We hope to extend the conversation and explore other models of educational transformation with this blog series. Enjoy!

References

Armstrong, P. (2010). Bloom’s Taxonomy. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved April 28, 2022, from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/.

Delors, J., Al Mufti, I., Amagi, I., Carneiro, R., Chung, F., Geremek, B., Gorham,W., Kornhauser, A., Manley, M., Padrón Quero, M., Savane, M. A., Singh, K., Stavenhagen, R., Suhr, M. W., & Nanzhao, Z. (1996). Learning: The treasure within. UNESCO.

El-Moslimany, A. (2018). Teaching children: A moral, spiritual, and holistic approach to educational development. International Institute of Islamic Thought.

Kearns, L. (2010). High stakes standardized testing and marginalized youth: An examination of the impact on those who fail. Canadian Journal of Education, 34(2), 112–130.

Mooney, C. G. (2013). Theories of childhood: An Introduction to Dewey, Montessori, Erikson, Piaget & Vygotsky (Rev. ed.). Redleaf Press Publisher.

Nasser, I., Cheema, J., & Saroughi, M. (2019). Advancing education in Muslim societies: Mapping the terrain report 2018–2019. International Institute of Islamic Thought. http://doi.org/10.47816/mtt.2018.2019

Nasser, I. Saroughi, M. Shelby, L. (2021). Advancing education in Muslim societies: Mapping the terrain report 2019–2020. International Institute of Islamic Thought. http://doi.org/10.47816/mtt.2019-2020-march2021

Schleicher, A. (2019). Helping our youngest to learn and grow: Policies for early learning. International Summit on the Teaching Profession. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264313873-en

Qurtuby, S. A. (2013). The Islamic roots of liberation, justice and peace: An anthropocentric analysis of the concept of “Tawhīd.” Islamic Studies, 52, 297–325.