In the third year of my Ph.D., I was discussing my research in comparative contemporary Islamic education with a Hui Muslim from China, and they asked me, “Are there even different kinds?” It is true that “tawheed” (acknowledging God’s existence and unity) is always at the core of an Islamic way of learning and teaching, yet, considering the immense cultural, historical, and geographical variation among Muslims, the straight answer to this inquiry is “Yes!”

First of all, the concept of education itself is a continually evolving process as the immediate needs of our societies adjust to changing global dynamics and advancements in technology. Faith-based teaching and learning practices, including Muslim schooling, are no exception to that. Islamic schools across the world may have their own definitions, practices, and goals of how teaching and learning should be with a diversity of approaches to prioritize; and that is not a new phenomenon. Starting in the 9th century through the 14th, scholars such as Ibn Sahnun, al-Jahiz, Ikhwan al-Safa, al-Farabi, Ibn Sina, al-Qabisi, Miskawayh, al-Ghazali, al-Zarnuji, Ibn Khaldun, and Ibn Jama‘ah in parts of the world spanning from North Africa to Central Asia produced various treatises on how education should be implemented within an Islamic context. In their perspectives, “Islam was viewed not as a discipline of religious beliefs and theology, but as a set of ideas, ideals, and ethics that encompass all aspects of human life” (Al-Sharaf, 2013, p. 278). The multi-dimensionality of human experience across geographies was already recognized in this period and prior, and Islamic education became a vibrant process, but not a static one, in its practice.

Those earlier scholars relied on transmitted hadith and the Quran in their formation of Islamic education theory. They were preoccupied with things such as teacher conduct, etiquette for learning and teaching of the religion, the relevance of other sciences, and the rules for production and transmission of scholarship, with a shared objective of understanding how a Muslim should learn without deviating from Islam (Cook, 2010). It can be difficult to discern whether their opinions represented a coherent “Islamic” educational theory both because of the large time span they covered and the different geographical regions they came from. Each produced a text based on what they deemed significant and/or necessary in their societies at the time to form a way of learning. None of them were trained in pedagogy as we think of it today, yet as Cook (2010) asserts, what they established shaped the future of Islamic education.

The foundation of their approach was that God and knowledge are interrelated. Hence, learning should lead one to God and strengthen faith in Islam. This would make it a necessity for members of the Muslim society to be accustomed to Islamic thinking and living in order for that society to flourish. However, beginning in the modern era, such concerns have been taken over by an anxiety to adjust to the needs of contemporary times. The colonization of several majority Muslim countries, modernity being negatively interpreted as Westernization, the separation of sciences now as secular subjects (even though they were already being taught prior to the modern era), the spread of socialist movements, the introduction of public schooling, and new technological developments have all together added new dimensions and priorities to education in the Muslim world. This resulted in changes to how faith-based schooling was practiced. The aims of schooling have become a matter of transitioning of Islamic societies from more of a conventional one to a modern model where “critical and scientific thinking” is valued (Rohman, 2017, p. 163).

This new approach has had its consequences. As Rahman (1998) argues, the outcome of modernization attempts has only created a paradox to modernity where the focus has been on re-construction of an Islamic philosophy from the past instead of focusing on the future. Yet, neither education nor religious education consists solely of kuttab/maktab or madrasas any longer. There are Quranic schools, weekend schools, homeschooling, school subjects dedicated to instruction of religion only, private K-12, public vocational schools, and higher education institutions all representing different forms of Islamic schooling practices across the Muslim world today. Some of them emphasize religious subjects, while some have added on sciences as secular subjects, with some others attempting to have an approach similar to medieval times where learning across various subject areas happens in accordance with a strictly Islamic focus. Islamic texts and teachings comprise a unique foundation for all of these categories defined by the educational needs of the Muslim Ummah (Shah, 2014).

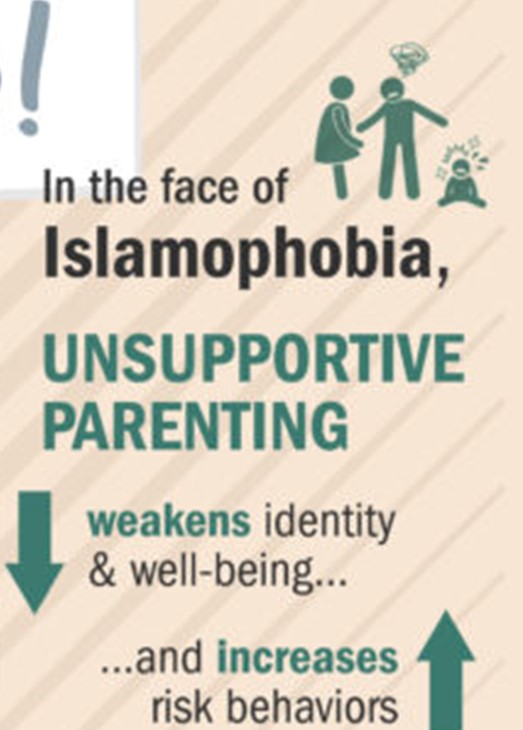

Overall, the “Islamic way” of learning and teaching is a complex phenomenon that requires institutions at the K-12 and post-secondary levels to respond to the needs of communities, wider societies, eras, national values, modernization efforts, globalization trends, and technological advancements. This is due to the simple fact that every society is unique in its structure, history, and its relations with the rest of the world. Forms of Islamic schooling that may work in the United States will have to go through several adjustments and changes to be implemented in German, British, Turkish, Nigerian, Indonesian, etc. contexts. Practices that worked four decades ago may need to be re-formed now. Regardless, such an education is generally deemed necessary either by the state, by communities, or by individuals as the venue for a Muslim identity to be formed. The shared goal of Islamic education is a strengthened sense of identity and understanding of the world around them, though approaches will vary depending on the community in which educators are working. Accordingly, despite having common aims and objectives (e.g., strengthening Islamic faith and identity) at the core, Islamic education in practice differs from one community, region, and nation to the other. We should be mindful of this notion when considering its evaluation and assessment, and a fair understanding of its associated societies.

References

Al-Sharaf, A. (2013). Developing Scientific Thinking Methods and Applications in Islamic Education. Education, 133(3), 272–282.

Cook, B. J. (2010). Introduction. In B. J. Cook (Ed.), Classical Islamic foundations of educational thought (pp. ix-xxxiv). USA: Brigham Young University Press.

Rahman, F. (1998). Islam and modernity. In Kurzman, C. (Ed.) Liberal Islam: A sourcebook (304-318). New York: Oxford University Press.

Rohman, M. Q. (2017). Modernization of Islamic education according to Abdullah Nashih Ulwan. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, 125, 163-167.

Shah, S. (2014). Islamic education and the UK Muslims: Options and expectations in a context of multi-locationality. Studies in Philosophy & Education, 33(3), 233-249.