American Muslims are split between those who attend the mosque at least once a week (45%) and those who attend only for Eid or even less (40%) (Pew Research Center, 2007, 2011, 2017). To explore why some Muslims are engaged in their communities—what I call embeddedness—while others stay away, I conducted life history interviews with 80 adult Muslims in 2016/2017 and 2021/2022. I limited my sample to those born between 1971 and 1985, who grew up in the United States, and resided in NY, NJ or CT. I purchased data from a firm that uses a global name algorithm to identify voters with likely-Muslim names. I randomly selected a subset of this sample and invited them to participate in life history interviews. Life history interviews are designed to capture events over time, gathering as close to longitudinal data as possible. Interviews focused on people’s experiences in their communities and their relationships with Islam across their lives, what I call trajectories of embeddedness.

Table 1. Participant Demographics

| Gender | Men – 42% Women – 58% |

| Highest Degree | High School – 11% College – 26% Post-Graduate – 63% |

| Marital Status | Never Married – 30% Married – 45% Separated or Divorced – 11% Other – 14% |

| Race/Ethnicity | Central Asian – 14% Arab – 27% South Asian – 42% Black – 8% Other – 9% |

Trajectories of Embeddedness

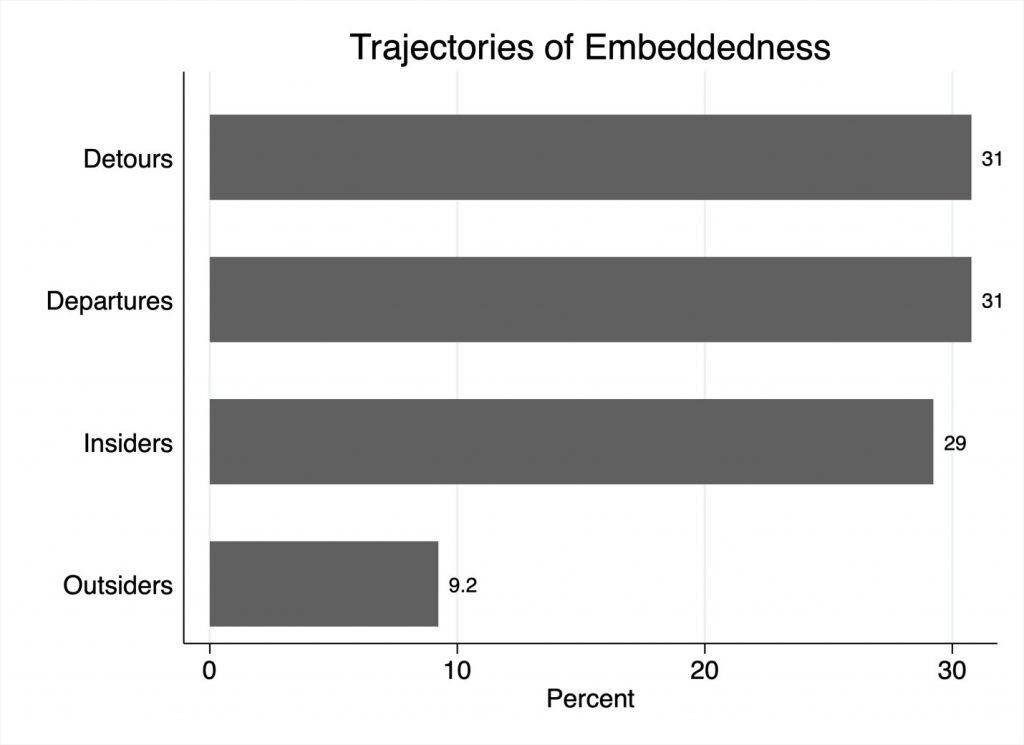

Four trajectories of embeddedness emerged in my data – Outsiders (9%), Insiders (29%), Departures (31%), and Detours (31%). Often children of mixed marriages, Outsiders’ parents rarely socialized with other Muslims or attended the mosque. These respondents remained peripheral to Muslim communities throughout their lives. In some cases, they did not identify as Muslim while in others they saw being Muslim as a racial and/or political identity (Love, 2017).

In contrast, Insiders (29%) were always embedded in Muslim spaces, from childhood into adolescence, early adulthood and up to the time of the interview. Departures and Detours, who together made up 62% of the sample, were respondents who were embedded with other Muslims in childhood but then disengaged with Muslim communities in adolescence and/or early adulthood. While Departures (31%) continued to build that distance over time, never re-engaging with other Muslims, Detours (31%) were those who returned in later adulthood after a period of drifting away from Muslim communities.

Embedded Childhoods & Compartmentalization

Insiders, departures and detours (91% of my sample) all started their childhoods embedded in Muslim communities, simply because their parents’ social lives revolved around other Muslims—either friends or extended family members. Embedded children usually received formal Islamic education either through weekend schools (62%) or full time Islamic school (10%); others had lessons at home with a tutor or with parents (15%). Since most children attended public schools (90%) where Muslims were a small minority, they usually also developed friendships with non-Muslims. These relationships tended to be compartmentalized. As one woman said, “I had my school friends, and I had my home friends.” Home friends were typically Muslim co-ethnics, whereas school friends were usually not Muslim.

Divergence at Adolescence

For departures and detours (62% of my sample), embeddedness in Muslim communities started to weaken as the balance between “Muslim friends” and “school friends” shifted in high school. Other friendships built around interests such as sports or school clubs took precedence over Muslim friendships. Teenagers stopped attending Sunday school and usually began decreasing their mosque attendance. For those who exited, leaving was not purposeful or ideologically motivated. Instead, respondents described their ties to Muslim communities simply fading away in adolescence.

Unlike departures and detours, insiders were those who stayed embedded during adolescence (29%). The teenagers who stayed embedded were exposed to multi-dimensional mosques which offered a lot more than prayer; they had youth groups, sports clubs, and outings. They gave young people opportunities to hang out with friends, making them—as one participant put it, “the place to be.”

Departures, Detours and the Gender Double Standard

In my study, even though women and men both disengaged from Muslim communities at similar rates during adolescence, their trajectories differed in adulthood, as shown in Table 2. Among departures or detours, only 35% of women return (i.e., detour) compared to 79% of men! Looking at the qualitative evidence, I argue this gender inequality is explained by differences in boys’ and girls’ experiences at home and in Muslim spaces.

Table 2 – Departures and Detours by Gender

| Detour | Departure | Total | |

| Men | 14 79% | 4 21% | 18 100% |

| Women | 11 35% | 21 65% | 32 100% |

| Total | 25 50% | 25 50% | 50 100% |

When boys strayed, parents and the broader community turned away and gave them privacy—an approach I call “don’t ask, don’t tell.” On the other hand, teenage girls faced intense scrutiny, surveillance, and pressure both at home and at the mosque. Parents monitored their behavior, who they spent time with, and what they wore. Likewise, girls received unwanted comments on their clothing and felt watched in mosques.

This double standard led to conflict with families. Girls on Departure trajectories outwardly fought their parents to establish more autonomy or started building secret double lives. For many, college was a chance to get away. Others pursued job opportunities or graduate school away from home. Since parents usually justified their monitoring and surveillance in Islamic terms and Muslim spaces like the mosque maintained the same double standard, many women came to associate this conflict not just with their families and communities but with Islam itself. As they gained more independence with age, many stopped attending mosque or began disassociating from Muslim institutions.

Men Returning and Women Staying Away

Over time, as second-generation Muslims reached their mid and late twenties, they started to settle down. For men, this often meant trying to return to the Muslim community. Many shed prohibited activities, like non-marital sex and drinking alcohol, and sought Muslim wives that would help them rekindle their religiosity. Men spoke of wanting to build households similar to those in which they grew up. When they returned, men were welcomed back and given the benefit of the doubt.

On the other hand, women faced a hard time re-engaging with other Muslims, even in the many cases when they wanted to. Some attempted to find Muslim partners but were met with unrealistic double standards. Others were already too turned off by their past experiences with Muslim communities to even consider a Muslim spouse. Among my participants, women were much more likely than men to permanently depart from Muslim communities and to marry non-Muslims.

Takeaways

There are several important lessons from these findings. 1) Community matters! Religiosity and engagement went hand in hand. Muslims with strong ties to other Muslims were more likely to have a solid belief in God, to pray, to fast, and to restrict from pork and alcohol. While there were many people in my study who were embedded with other Muslims but not very practicing, over time there were none who maintained religious practice without other Muslims. 2) Gender double standards harm women’s ties to Muslim communities. The more monitoring and surveillance women experienced, the more likely they were to leave and the less likely they were to come back.

References

Love, E. (2017). Islamophobia and Racism in America. New York University Press.

Pew Research Center. (2007). Muslim Americans: Middle Class and Mostly Mainstream. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewresearch.org/2007/05/22/muslim-americans-middle-class-and-mostly-mainstream/

Pew Research Center. (2011). Muslims in America: No Sign of Growth in Alienation or Support For Extremism. Pew Research Center.

Pew Research Center. (2017, July 26). U.S. Muslims Concerned About Their Place in Society, but Continue to Believe in the American Dream. Religion & Public Life. http://www.pewforum.org/2017/07/26/findings-from-pew-research-centers-2017-survey-of-us-muslims/