Dr. Ellen McLarney Talks About the “Soft Force” of Egypt

The International Institute of Islamic Thought (IIIT) invited Dr. Ellen McLarney on Mar. 10, 2016, to discuss her book Soft Force: Women in Egypt’s Islamic Awakening, which was inspired by Heba Raouf Ezzat’s al-Mar’a wa-l- ‘Amal al-Siyasi: Ru’ya Islamiyya [Woman and Political Work: An Islamic Vision], published by IIIT in 1995. Dr. McLarney highlighted this connection and expressed her happiness at the opportunity to visit IIIT.

Dr. Ellen McLarney is an Assistant Professor of Arabic Language, Literature and Culture in the Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Department at Duke University. She has been actively involved in the Mellon Foundation’s Humanities Writ Large initiative at Duke University through interrelated projects on “Islamic Humanities,” “Islamic Media,” and “The Art of Revolution: The Arab Spring.” She also has secondary appointments in Women’s Studies and International Comparative Studies, and has directed the Arab language program at Duke.

Dr. McLarney began her lecture by discussing the origins of her book, Soft Force: Women in Egypt’s Islamic Awakening (Princeton University Press). Dr. McLarney’s title is derived from a concept that Heba Raouf Ezzat analyzes in her book called “soft force” or “quwaha al-na’ima.” This concept of “soft force” was Ezzat’s way of including women in the discourse of nonviolent jihad in Islam. Dr. McLarney applied this idea in her book to women in Egypt using “soft force” as a means of achieving an Islamic awakening that put women’s rights and the family at the center.

Ezzat’s “soft force” was a reinterpretation of jihad within a feminine framework to allow women to take part in the formation of an alternative to the authoritarian state. Essentially, Ezzat argued that the family was emblematic of the state and the relationships functioned similarly to those in a state apparatus. For example, the relationship between a wife and husband was agreed upon in a pact similar to bay’a. The wife agrees to allow her husband to have governing rights over the family whereas the husband has a responsibility to make decisions and govern in a way that is beneficial for the family.

Bay’a is the first of four main political principles from the Islamic intellectual tradition that connect “the sphere of the Umma” and “the sphere of the family.” Bay’a is an “election of the Caliph” through a “contractual agreement” between the elected and the electorate, which in this case are the husband and wife. The second principle is al-wilaya al-‘amma, defined as “public leadership,” which falls under the responsibility of the husband. As a result of the bay’a or contractual agreement he becomes the leader of his family fulfilling the second principle. Shura is the third principle, which is the “consultation representing the Umma’s participation in political administration.” This relationship is demonstrated in the family through the husband’s consultation with his wife and children. Finally, the last principle is jihad, which is demonstrated through the “soft force” that the wife embodies.

Dr. McLarney further elaborated that this particular interpretation of jihad by Ezzat was “a means of bringing down a tyrannical government through nonviolent tactics like civil disobedience and (social, economic, and political) noncooperation” (156-57). Her book focuses on the 2011 revolution in Egypt at which time Ezzat published writings calling for “soft force” against the “strong force” of the “weak state.” Ezzat’s call for “soft force” in response to the “strong force” of the government resulted in McLarney’s in-depth analysis of how Egyptian women used this concept to “oppose secular dictatorship and articulate a public sphere that was both Islamic and democratic.”

McLarney also pointed out in her lecture that the 2012 Egyptian Constitution was the first time in Egyptian history that women were given unequivocal rights that were equal to men (Fifth Principle). Additionally, she highlighted that the eleventh principle of the 2012 Egyptian Constitution mentioned “soft force,” giving evidence of the impact of Ezzat’s writings.

Dr. McLarney concluded her lecture by reviewing six types of jihad as interpreted by Ni’mat Sidqi in Jihad fi Sabil Allah. These six types were “of the self,” “of the body,” “of the tongue and pen,” “raising and educating children,” “of religious education” and lastly “of motherhood.” These types of jihad indicate that women have already been participating in jihad through their household duties and obligations by being mothers and educating their children.

The lecture was followed by a Question and Answer session that concluded in a book-signing during which Dr. McLarney personally engaged with audience members.

Recommended Posts

Exploring Bioscience & Islam Seminar Series

May 21, 2025

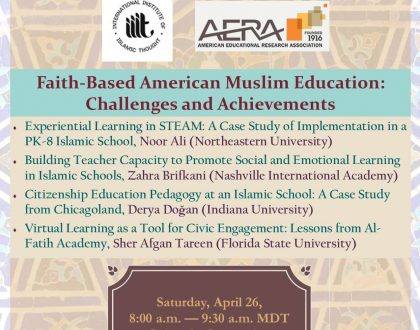

IIIT at AERA 2025 Annual Meeting

April 14, 2025

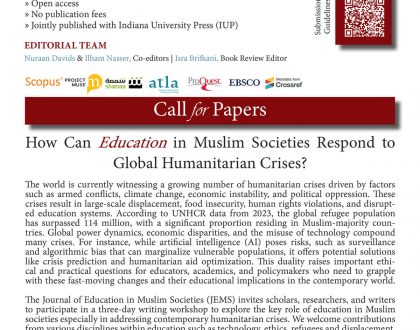

JEMS – Call for papers

April 11, 2025