AEMS BRIEF #10: TOWARDS A MORE CULTURALLY RESPONSIVE RESEARCH PROGRAM

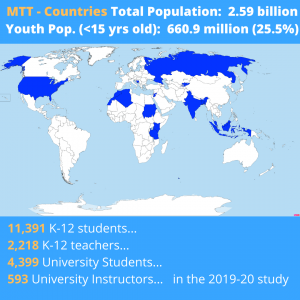

The Mapping the Terrain study took place in two phases, in 2018-19 and 2019-20, and surveyed 40,227 people in 16 countries on a host of social emotional skills and values. In many of our partner countries Mapping the Terrain was the largest, most comprehensive, and in some cases first scientific inquiry into non academic skills ever conducted. As a research team coordinating this project in so many different contexts, we gave special attention to designing an adaptable research framework that could be negotiated with the educational administration in each country. With plans to continue with the empirical research, AEMS is especially concerned with conducting quality research, and in this case, quality research also means culturally responsive research. Broadly, we aim to add a voice to the discourse of human development and holistic education beyond what is narrowly described by academic achievement data and in Western academic discourse. This is not just important for understanding and improving the educational experiences of students in diverse cultural contexts, but we believe that adopting such a culturally responsive approach to research can unlock new possibilities across the social sciences.

A large body of research exists on culturally sensitive and responsive practice and ways to address students’ needs who come from diverse backgrounds, religions, and cultures in the United States. These studies accept that socially-constructed differences between students can impact their learning and the ways in which they experience school. At the same time there are a great deal of studies on cross cultural research where differences between groups are suggested in values, traditions, and ways of thinking and meaning making. Ideally, these differences would be identified, investigated, and used to inform policy and practice. However, when looking at much of the literature, it is clear that the methodology and design, in many cases, doesn’t allow for deep engagement with how these differences are manifested and made relevant to local contexts around the world. In fact, there is a tremendous need for greater culturally sensitive and responsive measurement and research design, especially in international research settings. Meanwhile, large scale standardized tests such as the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), do not account for the embeddedness of learning contexts in local cultural practices at all. Even smaller educational studies are surprisingly parochial, as researchers typically apply constructs and measures derived from theories rooted in white, upper-middle class, American-centric ways of thinking. This constrains the kinds of questions that get asked, the ways in which researchers investigate them, and the interpretations of findings. In many cases this is done in the name of pursuing “scientific” and “neutral” measures of research. Such mindsets directly contradict the complex differences between contexts, cultures, and sociopolitical realities as they exist at certain points in time.

Nevertheless, there are some indications this is changing and researchers are being trained to detect the nuances of initiating international research agendas. Our ongoing research study “Mapping the Terrain” of well-being among Muslim youth in 15 countries set out to be deliberatively culturally-responsive to local contexts. This meant developing research measures that are both culturally sensitive and authentic and meaningful for local contexts. Based on three years of design, planning, and collaboration with local researchers, our experience shows there are concrete steps that research teams can take to be more culturally-responsive in their research.

First, culturally-responsive research requires building deliberately-diverse research teams that reflect at length, openly and in private conversations, about the potential cultural-sensitivity or problematic nature of constructs, measures, research methods and approaches. In our case, it was particularly important to recruit researchers with deep roots—through birth or citizenship, ethnic origin or long engagements—in a variety of national settings. Many of those researchers have been highlighted in our previous briefs, and their local expertise has been invaluable.

Second, authentic cultural responsiveness means that principal investigators and researchers must work with local communities at all stages of the research. At a minimum, researchers should send instruments to local community members to solicit feedback, pre-test measures, and pilot test questionnaires. Research teams should draw on the expertise of their diverse research teams and the local feedback to refine constructs and measures in culturally-responsive ways. In our case, knowing that we were working in many communities with strong collective norms and values, we were careful about selecting constructs that only measured individual traits.

In cross-national studies requiring the approval of local religious leadership—as is the case in some Muslim majority countries, it is also important to consult and communicate with key local elders and respected community members. For our study, we sent measures to a group of religious scholars overseas to elicit feedback and see how our focal constructs of empathy, forgiveness, moral reasoning and community-mindedness aligned with their understandings of Quranic values and teachings. We also conducted a focus group to make sure that our Western research-based definitions of constructs such as empathy were aligned with local understandings and religious grounding.

Creating authentic and sensitive measurements also required attending to the geopolitical conditions in each of the countries. In some places, we undertook a thorough review of survey instruments with our research teams overseas and removed items that would be problematic in local contexts. For example, in some places, items on religiosity or being dedicated to one’s faith could make respondents feel nervous or vulnerable.

Finally, being culturally-responsive researchers requires that researchers try to invest in local capacity by hiring local researchers and providing meaningful training. We also involved these local researchers in the dissemination of the results through academic presentations findings and interpretation and the publication of the results and research recommendations.

Some scholars may worry that being culturally-responsive will mean researchers need to change what they are doing to satisfy locals. This has not been our experience. On the contrary—not only was the substantive feedback useful as we aligned our measures to be more meaningful to local understandings and on-the-ground knowledge, but communication with local religious leaders, scholars, and community members was also a diplomatic exercise that helped ensure the blessings and goodwill of the larger community to our study. Negotiating the expectations of each party in the study and respectfully compromising when and where needed, without compromising the welfare of the participants, is culturally responsive research.

Committing to culturally-responsive research takes time, and it can be expensive. It demands good will, commitment, and thoughtful, time-consuming reflection. Funders should support the extra time and resources it requires—not only because it is ethically preferable, but also because it will help ensure that the data accurately reflects real issues on the ground, making the results more meaningful. If we fail, we will continue to miss tremendous frameworks that could help us understand social issues in a different way, and we will face a continuing myopia that says our way of doing things is the only way and our research is superior to others.

As this work continues, we hope that you will engage with us in thinking through the implications of this research. You can do that by responding to this email with any thoughts, by following us on Instagram (@iiit_insta) and Twitter (@iiitfriends), and by forwarding this message to anyone in your life who might find it interesting.

Thank you and all the best,

Alex Koenig,

Non-Resident Fellow in Human Development and Education Policy

The Advancing Education in Muslim Societies (AEMS) Team

The International Institute of Islamic Thought.

https://iiit.org/en/home/

***

This brief was written with contributions from Drs. C. Miller-Idriss and I. Nasser