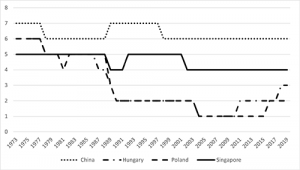

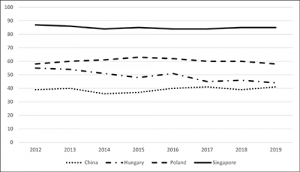

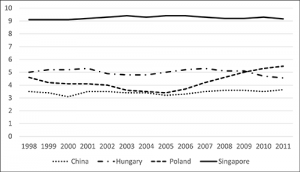

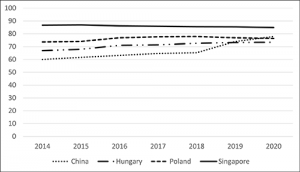

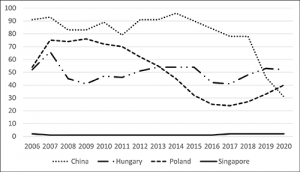

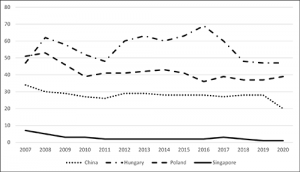

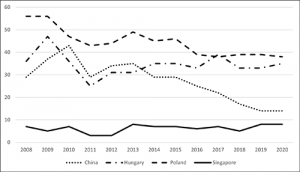

The above authors’ cautionary note was wise considering China’s dramatic innovation performance improvement during the past five years.[30] Singapore has fluctuated but remains solidly in the top 10. Poland’s innovation performance has improved under PiS rule, while Hungary’s ranking has remained around the same level under Orbán

To sum up this section, the four authoritarian capitalist countries surveyed in this essay perform as follows: Singapore leads the world when it comes to competitiveness and the ease of doing business. Singapore’s innovation performance is lower but consistently among the top 10 in the world. China’s ease of doing business performance and ranking as well as its innovation index ranking have improved dramatically in recent years. Hungary and Poland’s performances have wavered under right-wing populist rule, but they have not significantly deteriorated.

Conclusions and Reflections

Faced with the challenge posed by authoritarian capitalism, proponents of liberal democracy have consistently maintained that liberal democracy is better for business than authoritarian capitalism. We can see this in the following example:

Had Singapore been a liberal democracy, however, these difficulties might never have emerged in the first place. Even today, a freer society is likely to be more effective than more economic tinkering by the government in ensuring the country’s future prosperity. That is the economic case for liberal democracy in Singapore.[31]

Since these remarks were made a decade ago, Singapore’s performance has remained outstanding and China has made dramatic improvements. Hungary and Poland’s performances have fluctuated, but they have not significantly deteriorated under right-wing populist rule. In short: authoritarian leaders in these four countries have fostered a very good and increasingly attractive business environment.

The strong performance of authoritarian capitalist countries is not exactly news. After the Great Recession of 2008, there was recognition that, “One-party autocracy certainly has its drawbacks. But when it is led by a reasonably enlightened group of people … it can also have great advantages.”[32] Further, in light of Singapore’s success there is widespread acknowledgement that “liberal democracy is neither a necessary nor sufficient condition for good governance or prosperity.”[33]

I wish to clarify that I am not arguing that authoritarian capitalism is necessarily successful or good for business. Autocrats and right-wing populists can be harmful and damaging; when businesspeople perceive them in this way, they can mobilize against them.[34] But this should not be our default assumption as authoritarian regimes have become increasingly business-friendly across the world.

I am also not claiming that businesspeople would opt for an authoritarian regime if given a full menu of options. Political and civil liberties are important to citizens, and many businesspeople have an interest in a liberal institutional environment which empowers them politically. Ceteris paribus—all other things being equal—capitalist firms may well prefer liberal democracy to authoritarian governance. However, in the real world, all other things are not equal. Authoritarian governments may be sufficiently repressive that domestic firms in these countries do not have much of a choice other than working with the powers-that-be.

Businesses from Western Europe and the United States could exit from Singapore, Hungary, Poland, or China if their investments in these countries were not worthwhile or engagement in these countries was too unsavory on account of corruption, repression, or other grounds—but they do not. Businesses’ institutional preferences are malleable and business support can often be ‘bought’ with the right incentives, i.e. profits or rents.[35]

Political developments in recent years have significantly weakened the business case for liberal democracy and, as a result, proponents of democracy may need to re-think some of their arguments. As Cherian George has suggested, the “good governance” practiced by authoritarian states such as Singapore significantly weakens the instrumental justification for democracy.[36] Supporters of liberal democracy should not argue that liberal democracy is preferable because it is better for business than authoritarian capitalism, since it is far from obvious whether that is correct; in fact, the reverse may now be true.

The fact that authoritarian regimes have substantial business support suggests that democracy rests on a shaky political-economic foundation. To the extent that that is true, the future is wide open between alternative paths: a further deepening of authoritarian capitalism[37] could lead to more improvement of the business environment, or a move away from capitalism could help to save democracy. It is too early to tell if liberal democracy can be stabilized and reconciled with capitalism and made to flourish again, as was the case in the post-war order[38] or whether the road ahead is instead “a long and painful period of cumulative decay.”[39] In any case, supporters of democracy will need to make a stronger case for its intrinsic, rather than its instrumental value.[40]

Endnotes

[1] Francis Fukuyama, The end of history and the last man. Simon and Schuster, 2006.

[2] Ian Bremmer, The End of the Free Market: Who Wins the War Between States and Corporations, Penguin, 2010, 3.

[3] Larry Diamond, “Facing up to the democratic recession” Journal of Democracy 26.1 (2015): 141-155.

[4] Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt. How democracies die. Crown, 2018; Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014, and Thomas Piketty, Capital and Ideology, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2020; Adam Prezworski, Crises of democracy. Cambridge University Press, 2019.

[5] Daron Acemoglu and Suresh Naidu, “Democracy does cause growth” Journal of Political Economy 127.1 (2019): 47-100.

[6] Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson. Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. Crown Business, 2012.

[7] Ian Bremmer, The End of the Free Market: Who Wins the War Between States and Corporations, Penguin, 2010, 175.

[8] Dorottya Sallai and Gerhard Schnyder. “What Is “Authoritarian” About Authoritarian Capitalism? The Dual Erosion of the Private–Public Divide in State-Dominated Business Systems.” Business & Society (2019).

[9] Thomas Philippon, The great reversal: How America gave up on free markets. Harvard University Press, 2019.

[10] Netina Tan, “Singapore: Challenges of ‘Good Governance’ Without Liberal Democracy.” Governance and Democracy in the Asia-Pacific. Routledge, 2020, pp. 48-73.

[11] Raj Vasil, Governing Singapore: Democracy and national development. Routledge, 2020, p. 233

[12] Kent E. Calder, Singapore: Smart city, smart state. Brookings Institution Press, 2016: 164-165.

[13] Michael A. Witt and Gordon Redding. “Authoritarian Capitalism.” In: Michael A. Witt and Gordon Redding (eds.) The Oxford handbook of Asian business systems (2014), p. 26.

[14] David Shambaugh, China’s future. John Wiley & Sons, 2016.

[15] Hongyi Lai. China’s governance model: Flexibility and durability of pragmatic authoritarianism. Routledge, 2016.

[16] Margaret Pearson, Meg Rithmire, and Kellee Tsai. “Party-State Capitalism in China.” Harvard Business School Working Paper 21-065 (2020).

[17] Paul Lendvai, Orbán: Europe’s new strongman (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), p. 19, p. 150.

[18] Paul Lendvai, Orbán: Europe’s new strongman (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), p. 205, p. 53.

[19] Balint Magyar, Post-communist Mafia state: The case of Hungary (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2016).

[20] Kim Lane Scheppele, Worst Practices and the Transnational Legal Order (or how to build a constitutional ‘democratorship’ in plain sight) Background Paper: Wright Lecture, University of Toronto, 2016.

[21] Takis Pappas, Populism and Liberal Democracy: A Comparative and Theoretical Analysis (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), pp. 204-205.

[22] Péter Krekó and Zsolt Enyedi, “Explaining Eastern Europe: Orbán’s Laboratory of Illiberalism” Journal of Democracy, Volume 29, Number 3, July 2018, pp. 39-51.

[23] Jan-Werner Müller, What Is Populism? (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016).

[24] For a useful account of Poland, see Wojciech Przybylski, “Explaining Eastern Europe: Can Poland’s Backsliding Be Stopped?” Journal of Democracy 29, no. 3 (2018): 52-64.

[25] https://freedomhouse.org/reports/freedom-world/freedom-world-research-methodology

[26] https://www.transparency.org/en/news/cpi-2019-global-highlights

[27] See Gábor Scheiring, The retreat of liberal democracy: Authoritarian capitalism and the accumulative state in Hungary Palgrave, 2020.

[28] Paul Krugman, “Competitiveness: a dangerous obsession” Foreign Affairs 73 (1994): 28.

[29] Tsai, Kellee S., and Barry Naughton. “State capitalism and the Chinese economic miracle.” B. Naughton, KS Tsai, eds Naughton, Barry, and Kellee S. Tsai, eds. State capitalism, institutional adaptation, and the Chinese miracle. Cambridge University Press, 2015. (2015): 21.

[30] See also Li, Zheng, et al. “China’s 40-year road to innovation.” Chinese Management Studies (2019); and Yu Zhou, William Lazonick, and Yifei Sun, eds. China as an innovation nation. Oxford University Press, 2016.

[31] Marco Verweij and Riccardo Pelizzo. “Singapore: does authoritarianism pay?.” Journal of Democracy 20.2 (2009): 31.

[32] Thomas Friedman, “Our one-party democracy” New York Times 8 (2009): A29.

[33] Netina Tan, “Singapore: Challenges of ‘Good Governance’ Without Liberal Democracy.” Governance and Democracy in the Asia-Pacific. Routledge, 2020, 50.

[34] Daniel Kinderman, “German Business Mobilization against Right-Wing Populism.” Politics & Society (2020) https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329220957153

[35] Future research could aim to compare the profit rates of firms under authoritarian capitalism and liberal democracy.

[36] Cherian George, “Neoliberal “Good Governance” in Lieu of Rights: Lee Kuan Yew’s Singapore Experiment.” In: Monroe Price and Nicole Stremlau, eds. Speech and Society in Turbulent Times. Cambridge University Press (2017): 114-130.

[37] Peter Bloom, Authoritarian capitalism in the age of globalization. Edward Elgar Publishing, 2016.

[38] Sheri Berman, Democracy and dictatorship in Europe: from the Ancien Régime to the Present Day. Oxford University Press, 2019.

[39] Wolfgang Streeck, How will capitalism end?: Essays on a failing system. Verso Books, 2016, p. 72.

[40] Amartya Kumar Sen, “Democracy as a universal value” Journal of Democracy 10