Dr. Kecia Ali: Muslim Scholars, Islamic Studies, and the Gendered Academy

Professor Ali began her talk by tracing the origins of the AAR to 1909, when it emerged as a Protestant organization called the National Association of Biblical Instructors (NABI). It was only in the 1960s, after a number of internal debates, that the organization assumed its current title. This shift, however, came with new challenges and debates: Was the AAR to welcome only theological and confessional approaches to the study of religion? What of critical-analytical and political approaches? Professor Ali – an AAR member of almost two decades – emphasized that the assumed bifurcation between the two continues to represent a wider problem.

As Muslims became increasingly involved with the AAR after the 1960s, criticisms arose from two parties simultaneously: non-Muslim academics concerned about maintaining ‘non-biased’ scholarship, and Muslims worried about the potential for “inappropriately constructed Islamic theological work” taking place outside of conventional centers of Islamic learning. The latter worried AAR would be “run by a cabal of progressive Muslims with activist agendas,” and some even went so far as to decry the alleged heterodoxy (and sometimes even “apostasy”) of Muslim scholars affiliated with the AAR. The conservative critics of the former category instead emphasized the necessity of “safely critical” studies of religion, characterized by supposed moral neutrality and analytical distance. Dr. Ali problematized these accounts by demonstrating the (gendered) workings of power in both contexts.

Beyond challenges within the AAR, the general decline in public research funding, the crisis of “adjunctification”, recent threats to Title IX protections, and the shortage of tenure-track positions are all issues that disproportionately and negatively impact women in the academy. Through mechanisms like gatekeeping tenure committees, ever-changing “standards of excellence”, all-male panels, and discriminatory funding agencies, the (neo)liberal university maintains itself as a site of institutionalized sexism. However, as Dr. Ali suggested, to speak only of these mechanisms is to under-emphasize other sites of gendered contestation, including recent and ongoing public accusations of sexual harassment, abuse, assault, and rape within and beyond the academy.

The most technical part of Dr. Ali’s talk, however, focused on the politics of citation. In this portion of the lecture, Professor Ali discussed four books by three well-known Muslim male scholars and noted the shockingly low citation of female scholars (Muslim and otherwise) in each. In one case, female authors comprised a little over 1% of the works cited. Dr. Ali asserted that the widespread tendency to frame the findings of Islamic Gender Studies and its emerging canon as ‘common sense’ highlights the devaluation of women’s scholarly (and other) work.

Dr. Ali traced this form of devaluation in 1980s media representations of Lois Lamya Al Faruqi – the late musician, expert on Islamic art, and professor at Temple University. While few newspaper-references to her husband Ismail Al Faruqi (a co-founder of IIIT and the Study of Islam Unit at AAR) mention her, Lamya Al Faruqi’s accomplishments frequently appear peripheral and sometimes even invisible compared to those of her husband. By centering the voice of Lamya al Faruqi, Dr. Ali redefined IIIT’s annual Al Faruqi Memorial Lecture and situated it within ongoing and timely conversations in Islamic Studies focused on gender, power, and equity.

Recommended Posts

Exploring Bioscience & Islam Seminar Series

May 21, 2025

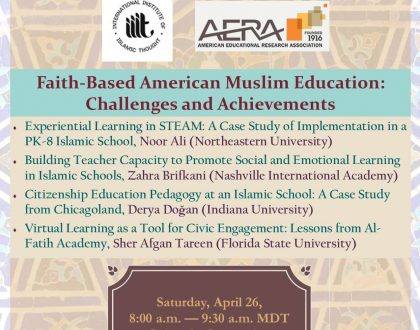

IIIT at AERA 2025 Annual Meeting

April 14, 2025

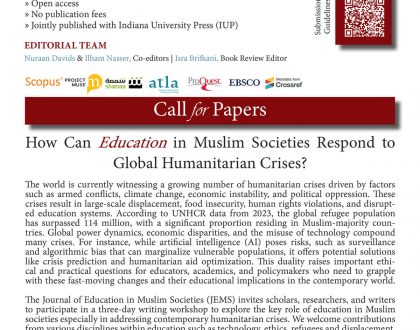

JEMS – Call for papers

April 11, 2025