AEMS BRIEF #2: EMPIRICAL RESEARCH IN MUSLIM SOCIETIES: METHODS AND SCOPE

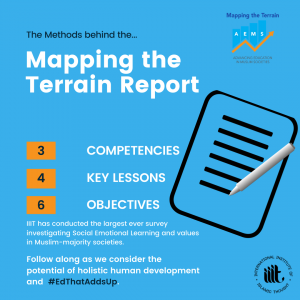

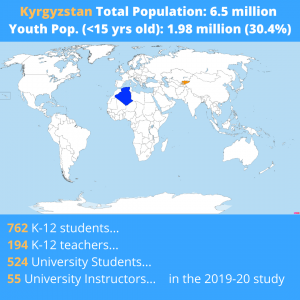

The Mapping the Terrain study took place in two phases, in 2018-19 and 2019-20, and surveyed 40,227 people in 16 countries on a host of social emotional skills and values. In many of our partner countries Mapping the Terrain was the largest, most comprehensive, and in some cases first scientific inquiry into Social Emotional Education (SEE) ever conducted. As a research team coordinating this project in so many different contexts, we gave special attention to designing a sensitive research framework that could be adapted a bit in each country. Researchers who are considering their own work in these systems may benefit from some of our lessons learned:

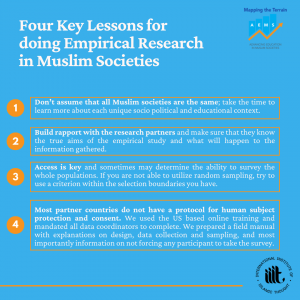

- Don’t assume that Muslim societies are the same; take the time to learn more about each unique socio political and educational context.

- Build rapport with the research partners and make sure that they know the true aims of the empirical study and what will happen to the information gathered.

- Access is key and sometimes may determine the ability to survey the whole populations. If you are not able to utilize random sampling, try to use a criterion within the selection boundaries you have.

- Most partner countries do not have a protocol for human subject protection and consent. We used the US based online training and mandated all data coordinators to complete. We prepared a field manual with explanations on design, data collection and sampling, and most importantly information on not forcing any participant to take the survey.

With these contextual lessons in mind, the objectives of the empirical research were identified as follows:

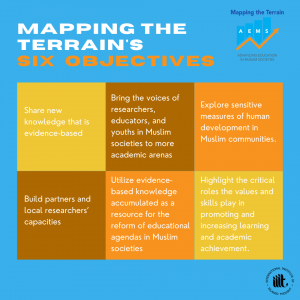

- Share new knowledge that is evidence-based through surveying attitudes and

perceptions using quantitative research methods.

- Bring the voices of researchers, educators, and youths in Muslim societies to the academic arenas in the United States and other Western and non-Western countries.

- Explore sensitive measures of human development in Muslim communities.

- Build partners and local researchers’ capacities (for example, providing training on sampling methods and ethical use of human subjects).

- Utilize evidence-based knowledge accumulated as a resource for the reform of educational agendas in Muslim societies, thus contributing to the design and implementation of learning standards, policies, pedagogy, and curriculum.

- Highlight the critical role/s the values and skills play in promoting and increasing learning and academic achievement.

Broadly, we add a voice to the discourse of human development and holistic education beyond what is narrowly described by academic achievement data. Behind this test-driven paradigm are the same neoliberal forces flooding the education market in so many countries with one-size-fits-all policies and pro-market agendas driven by major funders and special interest groups (Carroll & Jarvis, 2015). The selection of the human development model to ground this study is a result of thorough reviews of the achievement literature and an in-depth investigation of models that take a more comprehensive and inclusive approach to reform. The model we use highlights certain skills worthy of investment to benefit the psychosocial aspects of learning and wellbeing. Governments emphasizing only academic scores and standardized testing are losing the battle on the social, emotional, and values needed to guide youth and improve their lives (Kearns, 2010). Values in this study may be grouped into three sets of competencies identified as critical for transformation: (a) open-mindedness (constructs such as meaning making and problem solving), (b) responsibility (e.g., emotional regulation, self-efficacy), and (c) a sense of a collaborative collective (e.g., sense of belonging, collectivist orientation). Further values and competencies will be explored in greater depth in future briefs.

Sampling and Measurement

We examined the demographic variables of our respondents and built three Structural Equation Models (SEM) to analyze our data. On all three models, measure reliabilities were high, suggesting well performing translations and adaptation of the scales in the target Muslim societies. There were no significant differences on the constructs based on demographic variables such as gender and age. This study sampled mostly youth who are younger than 18

(56%). The next largest age group of students were young adults aged 18–24 (28%). Among the adults, the participating sample is highly educated, with most schoolteachers (72%) holding a bachelor’s or master’s degree and most university instructors (75%) holding master’s or doctoral degrees.

Of special interest within the SEM model is the result on the individualistic versus collectivistic measure which suggest that the participants in all groups and all countries tended toward a collective rather than an individualistic orientation, with the secondary students and teachers having slightly higher scores than the university students and instructors. This confirms the assumption that non-Western societies (at least in our sample) are more collective. Further research is needed to understand this cultural construct and ways it may be expressed or promoted. For more information on the SEM models, reliability measures, and limitations please see the full report.

As this work continues, we hope that you will engage with us in thinking through the implications of this research. You can do that by responding to this email with any thoughts, by following us on Instagram (@iiit_insta) and Twitter (@iiitfriends), and by forwarding this message to anyone in your life who might find it interesting.

Thank you and all the best,

Alex Koenig,

Non-Resident Fellow in Human Development and Education Policy

The Advancing Education in Muslim Societies (AEMS) Team

The International Institute of Islamic Thought