The Quest for Reading

Five professionals presented their research: Allison Ward Parsons (George Mason University), “Early Literacy Development through Interactive Reading”; Kathleen Ramos (George Mason University), “Best Practices in Reading Instruction with Adolescent English Learners (ELs) from Diverse Cultural and Linguistic Backgrounds”; Susan Douglass (Georgetown University), “Reading in the Content Areas”; Colette Chabbott (George Washington University), “Improving Early Literacy in Low-Income Majority Muslim Countries: Issues in International Development Agency”; and Saulat Pervez (IIIT), “The Landscape of Reading at a Private K-12 School in Karachi.” Amr Abdalla (director of assessment and evaluation, IIIT) moderated.

Ward Parsons, a former kindergarten teacher, opened by stating that early reading proficiency is a predictor of later academic achievement. Therefore, it is important to read with children as much as possible, for adding an interactive component to these read-alouds can truly enhance the child’s learning experience. If children are too young to read, parents can use picture books and have them locate the printed word in the picture and then in the text. A non-linear text with colored letters will help them learn how to illustrate their thinking via a picture or a drawing. Such an approach also helps them understand English-language text progression, regardless of their mother tongue – left to right, and top to bottom. Another benefit is that the teacher/parent can then guide them in terms of how to predict what will happen next, given that predicting is the culmination of prior knowledge and other comprehension strategies.

Ramos, who deals with teenaged students’ literacy, spent several years teaching Spanish and English as a Second Language (ESL) to refugees from Somalia, Myanmar, Nepal, and other places. Her goal was to get her students to love reading and embrace reading in English. She contended that one can learn to love reading by creating a culture of respect and rapport that allows students to make their thinking visible through interaction; having the teachers draw on their students’ social, cultural, linguistic and knowledge capital during reading and instruction; and blending cognitive, sociocultural, and critical literacy approaches into instruction so that they can become critical readers of multiple genres. To be successful, teachers need to ensure that students can actually read the text (via reading exercises and increasing one’s vocabulary), are interested in the text, can read it critically (viz., is it persuasive and subject to different interpretations, does it provide negative images of certain groups, and can they analyze it as a complete article?). To help them reach these goals, teachers need to encourage rigor (providing a wide variety of texts), relevance (to students, even if they are “uncomfortable” to teachers), and relationships (student-student and student-teacher).

Douglass called upon all teachers to improve their students’ reading comprehension, not just the official English teachers, for one cannot fully function in modern society without this skill. She explained how the “No Child Left Behind” policy had sidetracked the existing national standards as regards content area (at the elementary level) in terms of science and social studies (switching to a focus on math and reading). As a result, she pointed out that quite a few new high school students lack the necessary fundamental knowledge background and thus find it difficult, if not impossible, to keep up. Douglass suggested that this could be at least partially alleviated by having students teach each other, integrating the desired skills into the subject being taught, and replacing traditional turgid textbooks with “topic books.” She cited the 1990s “National Geographic Reading Expeditions” as a positive development in this regard. After stressing that students, especially those in elementary school, need enough time to absorb the content area and have to be made curious so that they will acquire the necessary skills, she closed by saying that the lack of a wide knowledge background has led to the current environment of fake news, non-belief in science, and other negative trends.

Colette Chabbot focused on the state of literacy in low-income countries. She reminded the audience of the need to “build” this ability early, for cognitive neuroscience shows that children learn more and quicker than do adults. Adults do not have nearly enough time as children do to practice and really learn, which is one reason why adult education programs often leave much to be desired. Notably, according to her, in very conservative Muslim-majority countries few people object to co-ed classes when confronted with scarce classrooms and teachers. Although the materials are relatively low cost and communities have many opportunities to help themselves, many children do not receive more than four or five years of formal education. While education is held in great respect, this “education” usually consists of rote memory based upon phonetic-only pronunciation and recitation without comprehension. There are also problems with the school’s distance from the students’ homes and their safety, their adherence to schedules and daily attendance, and the lack of concept of learning at one’s own pace. In addition, parents need to talk more with and to their children to help them increase their vocabulary, as this will help them in school. Experts also have to realize that there is no “one size fits all” solution.

Pervez presented her experiences at a private English-language PK-13 (British system) school in Karachi. In the early grades, teachers and parents actively engaged in the task of teaching children how to read, resulting in grade-level bilingual literacy. In the later grades, teachers and administrators verbally stressed the importance of reading, had an annual reading week, and made weekly visits to the library. And yet she noted a “dwindling interest in reading” and that verbal and writing skills were not “up to par.” When confronted, even by her own daughter, with the assertion that “books are boring,” it took her a while to realize that this was due to the students’ difficulty in navigating reading, inability to engage with the text, and having to deal with all-text books. Thus the “problem” was not the book, as the students would claim, but them. She also wondered why, despite high literacy rates in the urban areas, there was still no local reading culture. Given that reading is a “thinking activity,” fluent readers are able to simultaneously extract meaning as they read (“cognitive clarity”), whereas poor readers are not (“cognitive confusion”), a reality that impacts their overall levels of comprehension. Pervez pointed out that listening comprehension precedes reading comprehension, and thus the importance of reading aloud to children. Students who realize that reading can be “fun” will perhaps engage in sustained long-term silent reading, which has quite a few benefits: independent reading, fluency in conversation, a rich vocabulary, in-depth comprehension, creativity in composition – all of which enhance their development skills.

All of the speakers stressed reading aloud to children, acquiring critical thinking and reading skills, “amplifying” (get them to ask questions) instead of “simplifying,” and increasing interaction to determine their level of understanding. During the hour-long discussion, the audience of community education leaders and researchers raised many issues that were then addressed, such as instructing children in their mother tongue vs. English, previewing and monitoring Internet-based learning, and inspiring kids to read by building on their interests, such as graphic novels for boys in particular. On the whole, the attendees found the roundtable very useful and look forward to similar events in the future.

Recommended Posts

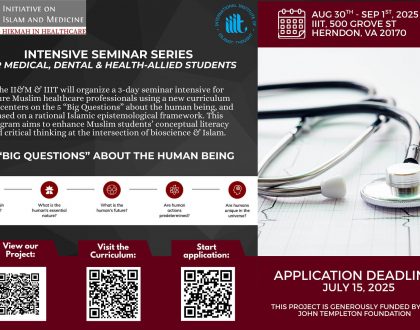

Exploring Bioscience & Islam Seminar Series

May 21, 2025

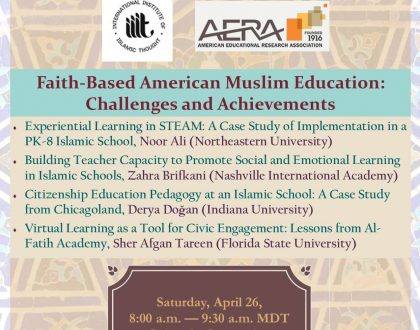

IIIT at AERA 2025 Annual Meeting

April 14, 2025

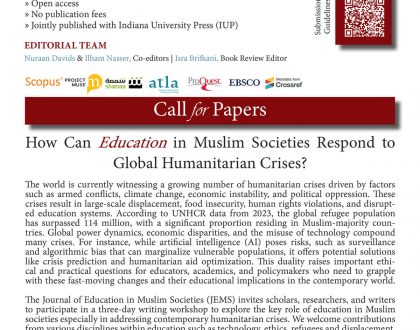

JEMS – Call for papers

April 11, 2025