Who am I? Where do I belong?

These are the existential questions faced during adolescence by all youth—and become particularly important questions for Muslim American youth as they come of age in a heated sociopolitical environment.

What helps Muslim youth thrive as they try to answer these questions and become the best version of themselves? What promotes their healthy well-being and successful thriving?

These are the questions that have been of interest to me for the past decade. In this blog post, I highlight some of the findings from my team’s work and conclude with some questions for all of us to consider as we help youth thrive. The research summarized here began with my dissertation study in 2013, continued through 2020 with my colleagues, Charissa Cheah and Merve Balkaya-Ince, and The Family & Youth Institute. We are currently collaborating with Baylor University on additional projects.

Although American Muslims are a heterogeneous group with varying backgrounds and experiences, this blog post only focuses on research among immigrant-origin American Muslim youth (i.e., first or second-generation South-Asian and Arabs) aged 14-22 years old. I discuss considerations for other sub-groups of Muslims in the Conclusion. Any use of the phrase “Muslim youth” refers to American Muslim youth (and not all Muslim youth globally).

What does Muslim youth’s well-being and mental health look like?

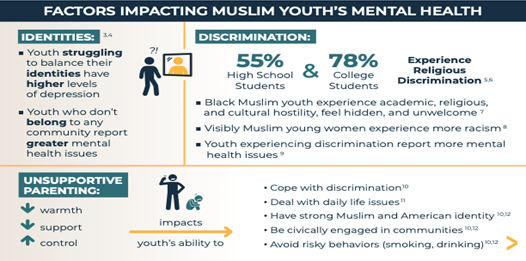

Muslim youth are experiencing mental health challenges, such as anxiety, mood disorders, eating disorders, adjustment disorders, and suicidal ideation (Basit & Hamid, 2010). However, Muslim youth also thrive and engage in their societies. Learn about some factors impacting their mental health in The FYI’s Muslim Youth Mental Health Fact Sheet (see excerpt below).

What helps Muslim youth thrive and promotes their well-being?

The focus of our work has been to understand factors that promote youth’s well-being and thriving. We specifically focus on identities as they are blossoming during adolescence and the role of parents during this stage. Our various studies on high schoolers and college students consistently find that Muslim youth endorse dual identities, reporting a strong sense of belonging to Muslim and American cultures (Balkaya, Cheah & Tahseen, 2019; Tahseen & Cheah, 2018), which was associated with the highest level of well-being. This means that youth who feel like they belong in their Muslim communities (masjid, friends, social circles) AND in their American communities (school, non-Muslim friends, social circles) have greater well-being.

Religious identity is protective. Interestingly, religious identity is protective for religious minority youth, similar to what others have found. A higher level of Muslim identity was related to less externalizing problems (e.g., smoking, drinking; Balkaya et al., 2019). Experiencing discrimination does not significantly impact youth’s Muslim identity (Balkaya et al., 2019). In fact, a strong religious identity actually empowers youth to be more engaged with their societies, especially in the face of discrimination. For instance, in one of our studies, we found that Muslim youth who identify strongly with their religion in their daily lives are more likely to be civic-minded and engage in civic behaviors, such as volunteering, belonging to or donating money to nonprofit organizations, and expressing their opinions on political issues (Balkaya-Ince, Cheah & Tahseen, 2020). These findings directly contrast all public narratives about how being actively Muslim pulls youth away from being American or contributing to American society.

American Identity is protective, too. In fact, youth who have a strong sense of religious identity may heighten their American identity to counter any Islam-based discrimination they experience. American identity refers to how youth believe they connect and belong to the mainstream culture in America, such as being with their non-Muslim friends or engaging in “American” extracurricular activities. When youth experience personal discrimination AND believe America to be an Islamophobic culture, we found that they respond by increasing their American identity, which protects them from engaging in risky behaviors. In other words, they express greater pride in being American and endorse American cultural beliefs and activities. Motivated to reduce the unfair treatment of all stigmatized Muslims, they may use their American identity as an empowering strategy and to reaffirm that Muslims do indeed belong to the American tapestry. In sum, this body of work shows that Muslim youth’s identities are complicated and should be treated as such in intervention and prevention programs.

Supportive Parents. The family is a central component in the lives of Muslims, with a lot of divine as well as prophetic emphasis and guidance on creating a healthy family unit. Based on this, our team focuses on the role of supportive parents in helping youth thrive. The parent-child relationship is critical in helping Muslim youth develop healthy identities and mental health outcomes. Supportive Muslim parents empower their children to have a stronger Muslim identity, engage in civic behaviors, and ultimately have greater well-being (Balkaya et al., 2019). Parents’ religious socialization efforts positively shape their children’s religious identity and religiosity, especially their day-to-day feelings about their religious group. These include talking to children about religion, engaging in religious practices together, encouraging friendships with other Muslim children, and engaging in social activities with Muslims. . Youth who received positive messages about Islam from their mothers had (1) more favorable attitudes about their religious group and (2) stronger beliefs that belonging to the Muslim group was an important part of their self-image on a daily basis (Balkaya-Ince et al., 2020). Parents can also protect youth from the adverse effects of discrimination. In one study, we found that mothers’ supportive conversations strengthened youth’s identities and well-being when they faced discrimination.

Conclusion and Next Steps

Our body of research for the past decade shows that Muslim youth are indeed thriving. Healthy identities with multiple groups serve as protective factors for youth when they experience discrimination. Parents play a crucial role in socializing youth and strengthening their identities.

However, not all Muslim youth are the same. They differ in individual characteristics, cultural backgrounds, generation levels, socioeconomic status, and the different environments within which they reside. We must consider the interaction between these factors to understand their experiences truly. Finally, American Muslim youth comprise many underserved subgroups that require special attention: young women, African American or Black youth, converts, and refugee youth. For much more information on the needs of these subgroups, please see The FYI’s State of Muslim American Youth report.

References

Basit, A., & Hamid, M. (2010). Mental health issues of Muslim Americans. The Journal of IMA, 42(3), 106–110.

Balkaya-Ince, M., Cheah, C. S. L., Kiang, L., & Tahseen, M. (2020). Exploring daily mediating pathways of religious identity in the associations between maternal religious socialization and Muslim American adolescents’ civic engagement. Developmental Psychology, 56(8), 1446–1457.

Balkaya, M., Cheah, C. S. L., & Tahseen, M. (2019). The role of religious discrimination and Islamophobia in Muslim-American adolescents’ religious and national identities and adjustment. Journal of Social Issues, Special Issue: To Be Both (and More): Immigration and Identity Multiplicity, 75, 538-567.

Tahseen, M., & Cheah, C. S. L. (2018). Who Am I? The social identities of Muslim-American adolescents. American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences, 35(1), 31-54.